FANTASTIC PLANET (1973)

“A sublime trip to a fine new world” is the tagline for Rene Laloux’s French-animated film FANTASTIC PLANET (1973). Initially, I thought the person who had come up with the line had never seen the movie. I know now I was arrogant in that assumption. The phrase does not accurately describe what it’s like to watch the flick, but rather succinctly summarizes the eventful resolution of the film itself.

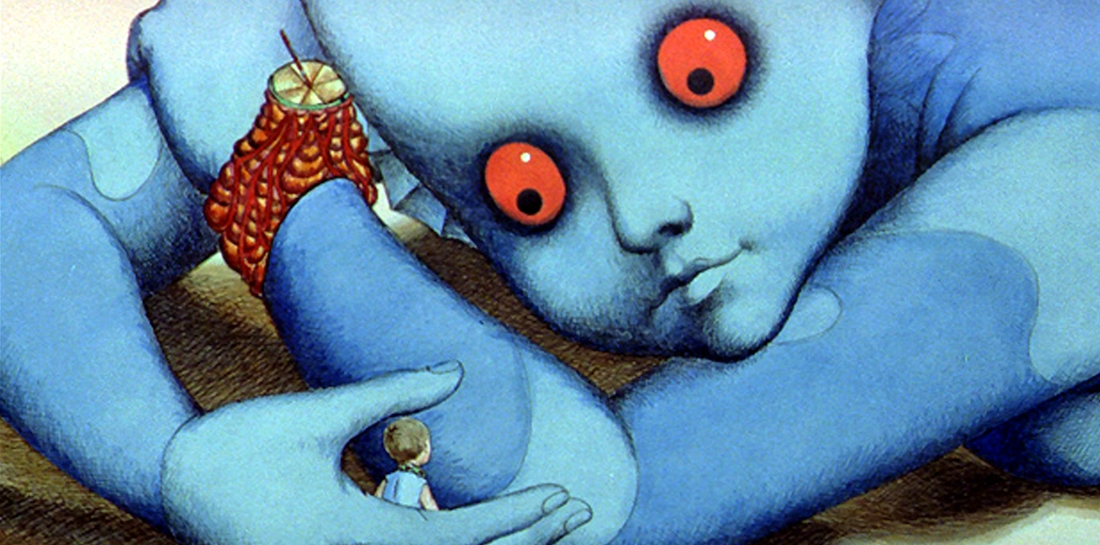

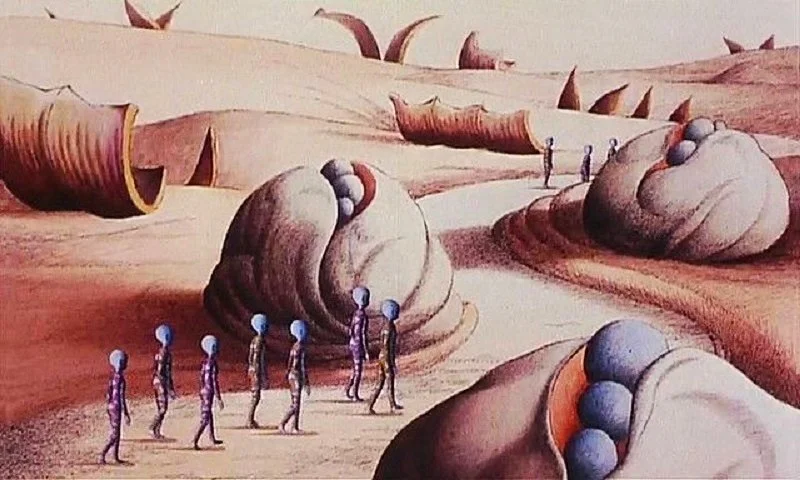

A surreal marvel, FANTASTIC PLANET hosts an array of visually stimulating settings that would kill a Victorian child. Roland Topor is to thank for the funky aesthetics and character design that make this film so unique. His surrealism and satirical proclivity shone throughout the film as interesting and odd flora and fauna decorate the planet Ygam. Critics have described FANTASTIC PLANET as psychedelic, hallucinatory, and avant garde, but so few sources cover the eerie atmosphere that is carefully crafted by Topor and Laloux. I think most people chalk the creep-factor up to its stylized animation, but that does a disservice to Topor. By the start of the film’s production, the illustrator had honed his ability to conjure anxiety and ambiguity and keep those haunting sentiments lurking in the viewer’s mind. The cutout animation style was ingenious, considering the limitations the crew had, and that method helped define the piece, distinguishing it from other animated films.

This distinction applied even more so from the—at times one-note—sci-fi genre. Unlike other entries in the realm of science fiction, FANTASTIC PLANET doesn’t depict a chrome crested megacity with neon light accents and ray-gun toting heroes. The planet Ygam is a much humbler setting with sparsely staged yet diverse life. The film’s pastel backgrounds accentuate its eerie tones and highlight the strangeness of the vibrantly colored alien subjects, Draags, creating an engrossing world.

Such groovy visuals had to come with an even funkier score. Alain Goraguer was a phenomenal jazz pianist and the composer for FANTASTIC PLANET, and I genuinely believe this movie would not be as iconic if it weren’t for his contribution. While researching the people behind this tantalizing picture I was amazed to find just how influential the music of this movie was. The soundtrack album, “La Planète Sauvage,” has been the inspiration for many bands and artists looking to experiment with psychedelic sounds and musical textures. Goraguer was particularly talented at creating pieces that were musically poly and heterophonic, allowing each song to be unique while simultaneously having a relevant consistency. The soundtrack greatly compensates for the lack of sound design the movie had, a choice that adds to the oddity and allure of the watch experience and greatly enhances each sequence.

One of the most charming scenes in the whole movie depicts everything the creators got right. When the young Draag Tiwa is applying makeup to look like Terr, her pet Om (the Draag term for humans), the young boy pranks her by switching the bottles of facial cream and eyeliner. From the top down everything about this section is brilliant. The characters move with surprising fluidity considering the cutout animation style. The funky, psychedelic, ‘70s jazz score punctuates every action and reaction. Tiwa, simply amused by her pet, fails to realize just how clever and adaptive Oms are. This small instance carries its significance throughout the rest of the runtime as the Draags constantly underestimate the capabilities of the Oms who, historically, had been written off as pests. The narrative of FANTASTIC PLANET forces its ‘Om’ audience to witness what it’d be like if they were treated like any other animal.

If you hadn’t already picked up, the name of the game is anthropocentrism, the idea that humans, by nature, hold the moral and intellectual high ground and, therefore, are the only beings capable of structuring how the world should work. The Draags are a clear representation of how folks tend to organize hierarchies with the intention of creating civility, order and, ideally, peace. In practice, these systems are more often used to justify the oppression of a society’s ‘undesirables.’ On Ygam, The Draags view Oms the way humans view Earthen animals—as either expendable nuisance or novelty. In one of the more mask-off scenes the Draags hold a conference and casually mention exterminating as many of the non-domesticated Oms as possible. Akin to PLANET OF THE APES (1968), the typical humanistic hierarchy is flipped on its head, painting a horrifying picture of what it would be like to be treated by… humans.

The way Laloux and Topor designed the world and politics of Ygam says more about people’s intrapersonal conflicts than just their relationship with nature. Anthropocentrism has the funny (funny perverse and horrifying, not funny ‘haha’) habit of justifying the creation of unfounded hierarchical structures as they pertain to race, religion, sexual orientation, gender expression, etc. A large part of the conflict in FANTASTIC PLANET is that the Draags write off the Oms even when faced with clear evidence that humans are not as mindless as they think. The cognitive dissonance grows as the Draags double and triple down on the idea that all they have to do to regain the status quo is eradicate the human population on Ygam. Truly, it isn’t until the Draags themselves are faced with extinction that they even begin to consider trying to effectively communicate with the oppressed caste they’ve created. The fact that the conflict got as bad as it possibly could be before being resolved would almost be funny if it weren’t such a painfully accurate depiction of humanity.

There is also an emphasis on the concept of mutual destruction, very thematically appropriate considering this movie came out during the Cold War. I have a slightly tweaked interpretation, if you’d humor me (not like you haven’t already considering you got this far). There are several moments in the film where both the Draags and the Oms assert that there is no non-genocidal resolution to coexistence, leaving both species to face total annihilation. The Draags are determined, at first, to preserve their society’s status quo until their safety is threatened, while the Oms fight for their survival from the very beginning. There is something cathartic about how Ygam’s humans develop their uncompromising resolve, preferring total annihilation to living as their oppressors’ playthings. The Oms strategically corner the Draags in a lose-lose situation while they themselves are either freed literally or metaphorically through the death of both parties.

While it heavily drifts from the typical motion picture experience, FANTASTIC PLANET is a great introduction for anyone looking to get into experimental films. It’s not too outrageous as to put off anyone unfamiliar with more avant-garde media, but it is incredibly interesting. If you’re like me, you’re going to love showing this film to your friends just to witness their initial reaction to the hypnotic visuals, quirky music, and iconic characters. FANTASTIC PLANET is the kind of movie you can easily rewatch again and again; every facet of the film offers the audience an opportunity to focus on its intricate details.

Before I leave you, I would like to add a flash warning around the fifth and sixth minute mark, and with that, I guarantee any viewer will be sure to find some aspect of Ygam and its inhabitants that’ll stick with them.