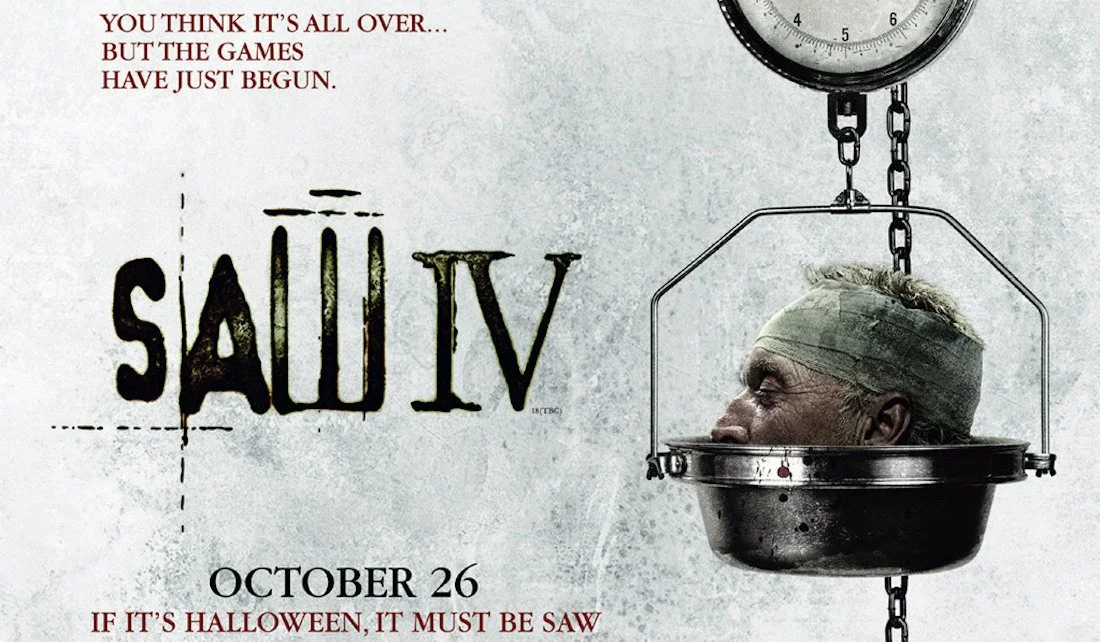

Fourths Of July: SAW IV (2007)

Of late we’ve seen the resurgence and renewed effectiveness of outrage marketing for film. During its run at Cannes, David Cronenberg’s CRIMES OF THE FUTURE was mythologized as so outrageous and grotesque as to prompt walkouts. Cronenberg himself then went on to tell interviewers that he expected more of these walkouts or outrage itself in response to his movie, which, he said, will be hard on people. The effect that Cronenberg’s sensationalized headlines had on theatergoers was that, even though it underperformed at the box office, more and more people (the average viewers, that is) were at least aware of this movie, not just die-hard Cronenberg fans, and now the film is appearing in best-of-the-year lists. In 2007, SAW IV committed a similar type of tactic that banked on the its outrageousness.

In 2007 at Comic-Con, director Darren Lynn Bousman and producer Mark Burg told audiences that the fourth installment in the Saw franchise had received an NC-17 rating by the Motion Picture Association (MPAA), the highest rating the MPAA would ascribe to a movie. The compromise after X, NC-17 is a rating that not only prevents those under 18 from seeing the movie at theaters, but also hampers distribution initiatives and advertising, which negatively impacts commercial performance. Bousman and Burg discussed whether they would edit their film to earn the milder R rating (which is what ended up happening). They also told audiences that the clip of SAW IV they initially wanted to share was rejected because it was “just too much,” going on to show a relatively less violent scene. The film was, ultimately, sold as being too much for Comic-Con. The effect of these stories was that SAW IV came to be the third-highest grossing film in the entire franchise, underperforming only to SAW II and SAW III, but certainly outperforming SAW V.

When you think of the Saw movies, you might think only of bodies being ripped apart, crushed under mighty weights, or burned alive. You might only recall those bits of bloody horror that seem like the reification of our worst fears—being thrown into a pit of needles, having our ribs pulled out, our mouth and eyes sewn shut, or our hair yanked with such force as to scalp us. It is for this violence that the fourth Saw movie received terrible reviews. Metacritic still has these reviews from 2007, with many singing the same tune:

“There is no narrative tension in the film, however, just a variety of grisly crucifixions. And the morality tales are blood-stained window dressing.”

“Since the thing is increasingly impatient to jump forward to the next big torture set piece, there isn't any time to establish anyone's character. Butcher shops are bloody, too, but they're not scary.”

“Everyone can agree, however, that this is probably the worst date movie ever. For non-sadists, at least.”

“It's a depressing experience to view something like SAW IV. It's not just the soullessness that's dispiriting, but the lack of invention.”

The film is a bloodbath, in other words. A curious indictment because, in comparison to the previous three films, the fourth installment is the first to thoroughly excavate the morality and inner workings of John Kramer (Tobin Bell), aka Jigsaw, which are revealed to be genuinely terrifying for how familiar they are. The fourth Saw movie is the most satisfying and horrific of the Saw films as it explains the mind behind all the torturous traps and games. SAW IV has a soul and perhaps it gets in its own way when it comes to communicating this to viewers, with all its squelching and splattering blood. Look past the sensationalized, headline-making violence and you will find a thoroughgoing morality, even if its makers are unsure of what to do with it.

Whether this morality is something worth writing home about is certainly debatable because it is one so familiar, ubiquitous, and pedestrian as to be boring. Kramer’s morality is such that, if this were a braver film, it would use its endemic horrific heft to add something to the discussion, to make an interesting statement as opposed to regurgitating something most Americans already know and are increasingly jaded by.

In SAW IV, we learn who exactly Jigsaw was before becoming bedridden because of cancer. Happily married to Jill Tuck (Betsy Russell), a physician running a clinic for recovering drug users, Kramer was a successful civil engineer. Jill was once pregnant but loses the baby after one of her patients slams a door into her belly. This event causes Kramer to become consumed by his anger, soon detaching from Jill completely as he learns of his cancer.

Isolated, he begins work on his traps for those he deems ungrateful for the life they have. Kramer aims with his traps to see if his subjects have the will to live. He doesn’t want to kill them, merely to test their will, hoping that once they emerge from his traps alive, they will value life. Often, he tells his victims that they have been born into various privileges, but still manage to live what he thinks are “bad” lives. Kramer wants his subjects to stop doing sex work, or selling drugs, or whatever it is that Kramer thinks is categorically bad, and he hopes that his tests will teach them to live a full life, which he would have been able to live had his son not been killed and had he not been diagnosed with cancer.

Kramer says he tests others’ will to live, but he only tests those he deems are not living life well (those guilty people not being present in the moment, those destroying their bodies with drugs, or partaking in sex work, or helping other bad people, etc.), hoping that his games might force conversion in his victims, as in the case of Amanda Young (Shawnee Smith).

In other words, according to SAW IV, Kramer as Jigsaw wants people to live life according to his rules, goodness is what he says it is, and badness is obviously illustrated by the various walks of life from which his subjects are dragged.

Jigsaw’s morality is very black and white and very Christian—and therefore violent, intolerant, and despotic.

Kramer might as well be punishing those who indulge in the “Seven Deadly Sins”: lust, gluttony, greed, sloth, wrath, envy, and pride. For example, in SAW III, the reason why Jeff Denlon (Angus Macfadyen) is put through Jigsaw’s games is because of his wrath after his son’s death, Jigsaw wants Jeff to practice forgiveness, to choose to not live in the anger and sadness of the past.

Max Weber in The Protestant Ethic And The Spirit of Capitalism writes that in modern society, profit is seen as a virtue, and this is because Protestantism and its branch-off ideology of Calvinism, tend to ascribe religious characters to worldly achievements. Calvinists believe that people are born into the world pre-determined by God whether they will be saved or damned — hints to the person’s having been saved or damned can be found in their material life. For example, the greater wealth a person possesses, the more likely it might be that this person was saved. This morality incentivizes good deeds in the material world to demonstrate to others that you are potentially saved. The more unfortunate the person’s lot and the less virtuous their behavior in face of this misfortune, the more it hints at God’s having destined them to be damned.

This thinking is also what undergirds the myth of the American Dream. To achieve that salutary dream of prosperity, one must simply work hard enough, and if you fail, then you simply didn’t work hard enough, the myth rationalizes. You might have been born damned, the prevailing morality says; if anything, you must keep trying, because being virtuous in face of material misery is also a sign of having been saved or potentially saved. This morality distracts us from questioning capitalism, the oppressive systems all around, and puts the onus of success and failure on the individual only.

This is a morality that makes assumptions and passes judgment on souls based on a person’s material presence in the world. SAW IV establishes that this is how John Kramer thinks. He seems to select those so obviously damned according to the Protestant Ethic (people living grimly dire lives, or, if they make a lot of money, it’s because they are also odious in other material ways), and tests whether they are truly damned or saved. He regains power from his own misfortunes by taking on the role of a beneficent god, plucking from the world those people he thinks are squandering their lives away, as though it were in their power to be successful and happy, and systems of oppression were not at work crushing everyone with unequal weight.

Kramer’s morality as enacted by his machines is of the Protestant Ethic and the American Dream: he chooses his victims based on the badness—lack of ostensible virtues in face of hardships or gains—in their material world. If you live through Kramer’s trap, then you had the will to survive and live well, because you are one of the saved. But if you fail, you earn death, and it’s your own fault, and Kramer takes a patch of skin from you in the form of a puzzle piece—you were missing the instinct to survive, Kramer says. For him, only those who have that special puzzle piece succeed through his traps, while those who fail were damned from the start.

To avoid Kramer’s traps, one must always be virtuous, regardless of whether one is poor or wealthy. One becomes Kramer’s victim when it isn’t clear to Kramer why one would not choose virtue every time. He seems to forget that society is broken, in the way capitalism ignores it has broken society, in the way that religion forgets we live in a society at all. If one survives Jigsaw’s flagellation, Kramer believes he has discerned that person worthy of salvation; he sees himself as a divine vetter, separating the damned from the saved, expediting judgment day and the annihilating machines of the American Dream.

Instead of working to fix the systemic issues that might lead to addiction and cycles of abuse, Kramer attacks the singular person for living a life that lands them in prison, he puts them through hell for ills he believes to be endemic to his victim’s being, an offshoot of their psyche, exemplified by their choices, as opposed to being symptomatic of a diseased society.

I don’t know if the film realizes that with Jigsaw they have personified the spirit of capitalism and the ethos of the American Dream, complete with a black and white, individualist morality. Again and again Jigsaw says that he provides his victims with choice, it is in their power to be free and safe, but this is also how capitalistic society works. We are told we are free to choose under capitalism, but choice between two shitty options isn’t much of a choice, is it? In Jigsaw’s puzzles, one must choose to either stab one’s eyes out or have one’s limbs torn from their torso. What kind of a choice is this?

SAW IV is the first in the franchise to deliver us Kramer/Jigsaw’s philosophy. And contrary to critics, this film does have a soul in it. But perhaps the film’s outrage marketing, its reputation for delivering unbridled gore, along with its admittedly dizzying and frenetic framing, distract from this heart embedded deep within the viscera. Because look between the oozing guts and blood and exploding chests and flying limbs, and you will find the spirit of the most destructive being the horror genre has produced to date: Jigsaw wheezing out capitalism’s steely, boring but mightily destructive soul.