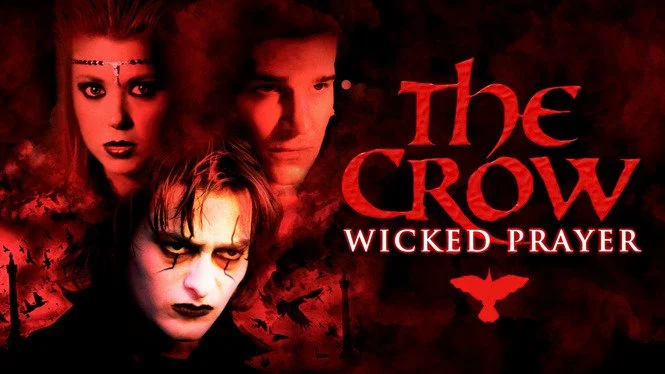

Fourths Of July: THE CROW: WICKED PRAYER (2005)

A Betrayal Of Brandon Lee’s Promise

Some movies begin to feel like home to me. When things get bad in the real world, when the tides of reality rend my psyche asunder, leaving nothing of my mind or personality to tether me to this plane, I have a precious few films I crawl into as though they were bed, a safe haven, their common thread being their clear-cut morality that isn’t too complex to follow, their beauty—cinematographic, actors’, sonic—a balm for swollen eyes. Such films don’t necessarily have to be categorically good, they just need to be good to me; meaning they have to harken back to the moment of my first watching, the moment when that amorphous sludge of my personality snagged at one of their aspects and clung tight, thus cultivating my taste. Their narrative, or holistic experience offers a world that at the end of its drama, at the end of all the tragedy of its plot, promises safety by virtue of its intuitive familiarity, something the real world cannot guarantee.

The Alex Proyas-directed THE CROW (1994) is such a film—one that reminds me of what is good, what I like, who I am—for its promise of a traditionally strong masculinity undergirded by a crucial vulnerability, a safety; it’s a fantastical promise that Brandon Lee and his Crow deliver stunningly, heartbreakingly. After all, why we like the stories and movies we like is because they show us the fulfilment of a fantasy we as viewers viscerally need to see fulfilled, even if it is fictional. It is for this reason that all THE CROW’s sequels feel like betrayals increasing in severity until 2005’s THE CROW: WICKED PRAYER, which is like an assault on the senses, a film whose existence I refuse to give the benefit of the doubt, I refuse to justify, because it quashes the promise of safe masculinity that Lee makes and fulfils in the original.

I would argue that the second and third films in The Crow franchise each deliver their unique spin on Lee’s Crow, mining the complex and textured character Lee portrayed for certain aspects and depicting them singularly. For example, THE CROW: SALVATION (2000) is the most compelling of the sequels, with Eric Mabius as Alex Corvis (the corollary of Lee’s Eric Draven) creating a character that is his own. Here, Mabius gives us a Crow who compellingly reiterates the cunning and playfulness of Lee’s Crow. Additionally, while the immediate sequel to the 1994 film THE CROW: CITY OF ANGELS (1996) is nothing to write home about, it does carry through on the first film’s gothic and grimy ambience, along with giving us a version of the Crow enacted by Vincent Pérez that is unique in a sense: Pérez underscores the sorrow and madness of Lee’s Crow.

THE CROW: WICKED PRAYER, however, is an abominable enigma with very little going for it.

In this fourth (and, so far, final) installment in the franchise, Edward Furlong portrays The Crow character, Jimmy Cuervo, and is woefully, embarrassingly miscast.

The film barely scans as a part of The Crow mythos, being more about the bad guys than it is about the figure of a man brought back to life by the fantastical power of a crow. It’s difficult to describe the plot because it’s mostly confusing when it isn’t horrifyingly offensive.

Directed by Lance Mungia, THE CROW: WICKED PRAYER takes place in a sun-baked mining town called Lake Ravasu, situated on an Aztec reservation. The Aztec tribe is positioned as wanting to close the mine and open a casino in its place, meaning that the local white miners will lose their jobs, accordingly, the miners are protesting. This is the dynamic the film inexplicably sets its plot. We meet David Boreanaz’s Luc “Death” Crash, the leader of a satanic cult, and his disciples War (Marcus Chong), Famine (Tito Ortiz), and Lola Byrne (Tara Reid), who is Luc’s girlfriend and in possession of a book of satanic prayers that contains a spell that will transfigure Luc into the antichrist.

To kick start the ritual, Lola and Luc need the eyes of Lily (Emmanuelle Chriqui), the daughter of Danny Trejo’s Padre Harold who’s the tribe’s chief, and the heart of her boyfriend, paroled convict Jimmy Cuervo (Furlong), respectively. Luc’s cult kills the two lovers, and he embarks on a journey that ends with his and Lola’s damned wedding. The ceremony is officiated by Dennis Hopper’s El Niño, a satanic preacher whose dialogue is seemingly strings of words pulled off Urban Dictionary and put into an order that the writers (Mungia, Jeff Most, Sean Hood) hope makes sense on the “streets.” Punctuating the cult’s endeavour to turn Luc into the antichrist are Jimmy’s attempts to avenge his and Lily’s deaths, and an incomprehensible amount of violence against Indigenous peoples (there is an exceedingly violent massacre at one point whose reason for being in the plot is still unclear to me).

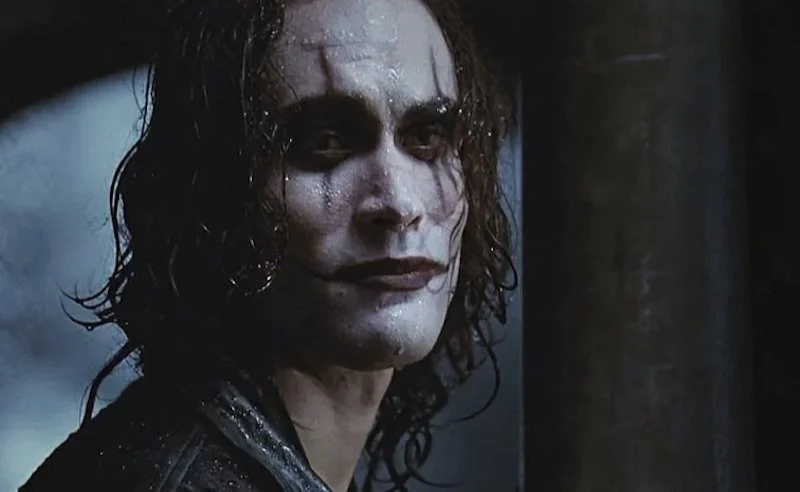

It is not exaggeration to say that Furlong’s Crow is at the periphery of this film. So much of WICKED PRAYER’s action follows the satanic cult that when Furlong does appear it’s almost a surprise. Oh yeah, this is a part of The Crow franchise, one thinks. Furthermore, Furlong is so miscast in this film that its own dialogue cannot escape noting it either. Though the actor would have been 28 in 2005, he cuts the figure of a teenager next to Chriqui’s bodacious and tanned Lily, a character who is pure and kind, existing only to bolster the conscience and purpose of Jimmy; pure eye candy, in lesser words.

Here, Furlong’s voice is the same as it was in TERMINATOR 2: JUDGEMENT DAY, still cracking as if from the effects of puberty; his Jimmy seems shy around Lily.

When he transforms into The Crow, Furlong does attempt to swagger in his raven-black ensemble, aping the confidence Lee wore effortlessly, but it scans as too artificial, seems too affected.

So much of Furlong’s Crow seems apologetic for his resurrection, for his presence on screen, and by extension unfit for the vengeance this character is all about. At the film’s end, Trejo’s Padre Harold asks how God could have chosen Jimmy for this noble fate of resurrection and vengeance. Furlong’s Jimmy shrugs haplessly, seeming spent from the effort the plot required of him. “I don’t know, she [Lily] picked me too,” he responds, as if he knows he is unworthy both of being The Crow and of Lily’s powerful love. Lee’s Crow acted, but only fuelled by anger and justice, Furlong’s Crow seems to bemoan the tasks thrown his way like a teenager bemoans taking out the garbage.

One cannot talk about this franchise, this particular movie and Furlong’s performance in it, without Lee’s Crow as a bedrock of comparison, for each sequel dared to recreate his character. This naivete and half-heartedness of Furlong’s performance, his unconvincing love, along with the youthfulness that his face possesses, which can’t help but be baked into his Crow, can’t help but appear on screen, come together to form a character who is a betrayal of the larger-than-life character Lee created. While Pérez and Mabius homed in on a single of Lee’s Crow’s aspects to simultaneously attempt at a distinct character than Lee’s Eric Draven while also gesturing toward their inspiration, even if inadequately, Furlong’s Crow is not only totally unrelated to the original iteration, but the actor also adds nothing new to the character to make it compelling in its own right.

WICKED PRAYER could have played up the aspect of unconventional masculinity through Furlong, there was potential for this in Furlong’s Crow’s androgynous look—this could have been an intensely interesting and almost subversive for its time avenue for the film to take. The film, however, doesn’t seem intelligent enough to pursue this idea beyond shrugs from Furlong—it seems to not have the backbone or the time in narrative space to do this because it’s more concerned with its “bad guys” and weird slurs against Indigenous peoples. The Crow seems to be a secondary character here. Jimmy is so effete as to be pathetic, needing intervention from the tribe and their guns to complete his diminutive hero’s journey.

Consider the massacre scene wherein Luc orders the murder of a group of Indigenous people who have congregated in their own space to celebrate their Raven’s Fest, having Famine shoot at people as they lie beneath a white sheet. Jimmy is there, but he doesn’t interfere, ambiently aware of what is about to go down, he chooses to throw quips at Luc and Lola instead, stepping in only to save a single child after the worst of the violence. Contrast this with the scene in THE CROW wherein Eric visits Funboy (Michael Massee), one of the men who raped and killed his fiancée Shelly (Sofia Shinas), and Darla (Anna Levine), Eric and Shelly’s young friend Sarah’s (Rochelle Davis) mother, as they’re in bed shooting up heroin. Eric tortures Funboy for information and then kills him, while Darla is a terrified bystander, cowering in the bathroom with a razor blade. Eric doesn’t kill Darla, but he also doesn’t leave without acknowledging her. Rather, he drags her to stand in front of the bathroom mirror with him, having her countenance her own doped-out face and sleepy, swimming eyes, the needle marks in the crook of her elbow, using his powers to pull the drug out of her veins. “Morphine is bad for you,” Eric says to Darla, and conveys to her that Sarah needs her more than she lets on. Lee’s Crow does good as he does bad to the evil ones, while Furlong’s Crow barely manages to destroy the bad guys at all.

What Furlong depicts, despite all his efforts, is a supernatural being whose heart isn’t in the task at hand—pun intended—and who accordingly hardly helms the film created in his name. Even immediately after watching WICKED PRAYER, one would be hard-pressed to recall Furlong’s definitive scenes or even what his Crow accomplishes. The love he has for Lily that is meant to be fuelling his lust for revenge is conveyed less than his tiredness to the extent one wonders what his motivation is at all. The weird creation that is Jimmy Cuervo seems a disservice to Lee’s Eric Draven, who dominates every scene he is in, to whom one’s eyes gravitate in frame after frame, whose at times charming at other times heart-breaking presence one craves when he isn’t there.

I don’t want at this moment to partake of the discourse around this film that speaks at length about how Lee’s THE CROW has a mythical aura to it because of the actor’s tragic death. Rather, I would like to look at Lee’s performance alone. I would like to celebrate the positive masculinity he depicts, I would like to celebrate his beauty, and how the fourth installment does gross injustice to the inimitable character Lee forged.

In face of Furlong’s despondency, I recall the tenderness in Lee’s Eric’s eyes and the half-smile on his lips as he says to Sarah “It can’t rain all the time,” with a desperate sort of love for her, a wish to be alive again.

I recall how small Eric looks when leaving Detective Daryl Albrecht’s (Ernie Hudson) apartment, when Detective Albrecht asks him if he’ll disappear out through the window, Eric says with a boyish grin, “I thought I’d use the door.”

These are aspects to Eric Draven that are all Lee’s own, for they lack the overzealous commitment to fit into a type that all the subsequent actors can’t but escape, which is why every sequel or remake of this movie will always be redundant. Lee’s Eric has a distinct personality composed of carefully selected traits, many of which seem to be determined by Lee’s physicality, that come together to make a nuanced personality, while all the subsequent iterations mine an aspect of Lee’s Eric and blast them singularly, garishly on screen.

Lee with his Crow created this beautiful play on the traditionally masculine hero, created this man who would fight for you, keep you safe, but wouldn’t patronize. He has kindness for you and for animals and for kids, but nothing but ire against evil—this was the promise of Lee’s Crow alone and that no other actor in this franchise has been able to fulfil.

This safety that discriminates against evil is why Lee’s THE CROW is an important haven for me, and why I feel betrayed by the fourth instalment: because it neglected to flesh out the character in the way Lee did, it hasn't shown this character the same respect Lee did. In face of all the films in this franchise, I can’t help but think of Brandon Lee, how he moves as Eric, how he wails, how his deep voice cracks, the jokes he makes with Albrecht, how his big hazel eyes glisten with tears when he looks at Sarah or Detective Albrecht, how he slumps onto the curb hugging his guitar because it connects him to life with Shelly. It’s impossible to not look at Brandon Lee when he’s on screen, he is so beautiful, so strong, so kind as The Crow. This is why all the sequels, any of its remakes that are rumoured to be in the works, will always feel like a betrayal to me.

By existing as part of this franchise, these movies pick up the promise of The Crow that Lee made to us, a promise of a tenderly tragic hero who through his vulnerability, the warmth of his love of goodness and love itself, gives us healthy masculinity unafraid to express strength alongside kindness. These movies then go on to quash the promise of this hero for the reasons illustrated above, but ultimately because they can’t possibly follow through on the contract. So many of Lee’s idiosyncrasies went into The Crow, and Lee isn’t with us anymore. Resurrection of this character is doomed to failure.