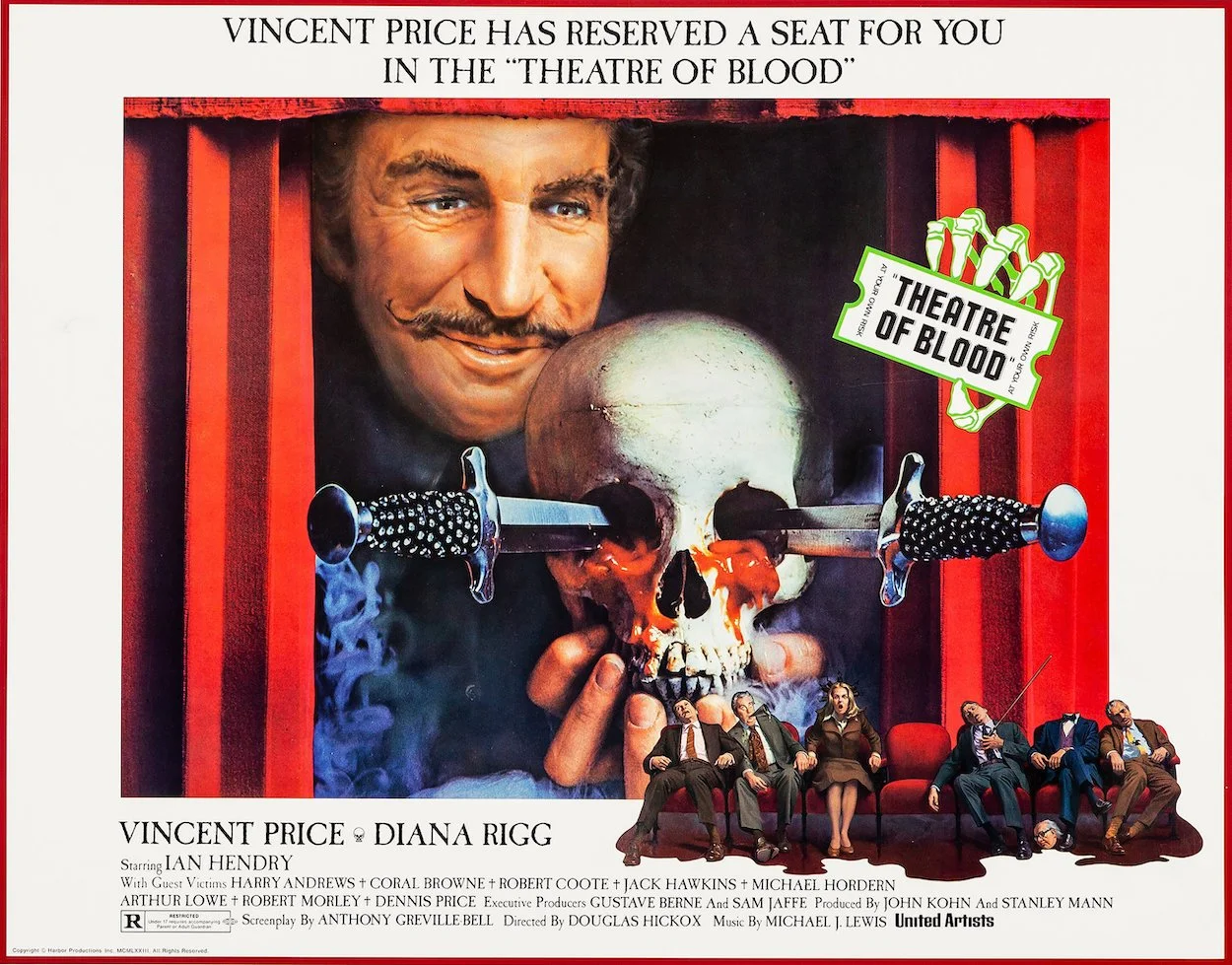

THEATRE OF BLOOD (1973)

A brief synopsis of 1973’s THEATRE OF BLOOD, directed by Douglas Hickox based on a script by Anthony Greville-Bell (which, in turn, was based on “ideas” by Stanley Mann and John Kohn)…

Vincent Price stars as Richard Lionheart, a stage actor who appeared in numerous productions of Shakespearean plays throughout his career.

After years of scathing reviews and no true recognition, a distraught Lionheart seemingly kills himself in dramatic fashion. Not long after, various critics who were harshest to Lionheart, and passed him over for a coveted critics’ award, are murdered in startlingly similar fashions to fates that befell characters in the very dramas they’d previously critiqued.

This article will guide the reader through each kill while lightly tiptoeing through the plot—mostly emphasizing the deaths’ connections to the bard’s works from which they spring.

Julius Caesar (George Maxwell)

By the time you realize the tides have turned on George Maxwell (Michael Horden), it’s already far too late for him. The contentious critic wasn’t someone to root for, as he is only too eager to poking and prodding at “squatters” who have taken up space in an empty tenement he owns (and plans to tear down). When those seemingly drunk homeless people drop their act, the change in mood is swift—this man is about to die and somehow, it’s personal. When he starts to back up, he looks for any friendly faces among those he just judged as unworthy. He finds none and gets stabbed repeatedly as he’s crowded against a clear tarp directly mirroring Julias Caesar’s stabbing—which is nicely and directly called out with the inclusion of a Julius Caesar poster shortly after the first death scene. That is one of the great things about THEATRE OF BLOOD: it isn’t hiding its homicidal adaptations of Shakespeare. This movie wears its camp on its sleeve and knows it can deliver its diverse set of deaths in creative ways.

Troilus And Cressida (Hector Snipe)

The hint towards Troilus And Cressida is a very quick glimpse within a newspaper clipping that shows the upcoming victim’s review of Lionheart’s performance in that play. The graphic nature of the death of the second critic, Hector Snipe (Dennis Price), is among the most disturbing in the film due to the playful nature of its build-up. All the background actors we saw mercilessly stab the previous critic are laughing and grasping at this man right after he was sprung from the basement confrontation with Lionheart, all while some silly tune is playing in the background. As soon as Lionheart finishes his speech, he spears the man through the chest. Unfortunately, even after death, this critic is dragged by a horse directly to the funeral of the previous critic, very similar to Hector’s stabbing and dragging-by-horse in Troilus And Cressida.

Cymbeline (Horace Sprout)

This one is probably my favorite kill of this film due to the absolute silliness of the actors using an oversized trunk as transport combined with the way Vincent Price hams it up while beheading Horace Sprout (Arthur Lowe), who apparently has been given ample enough anesthesia that Price can proceed with his decapitation without much interruption. If there was any doubt about this film being more of a dark comedy than straight-shooting horror, this critic’s demise served as a genre confirmation. In Cymbeline, the source material for this kill, the fight betwen Guiderius and Cloten culminates with a beheaded Cloten. While THEATRE OF BLOOD steers this death into a much more comedic direction, the influence of Cymbeline’s decollating remains.

The Merchant of Venice (Trevor Dickman)

Trevor Dickman (Harry Andrews), our fourth critic/victim, is led onto a stage amid a speech from The Merchant Of Venice before being asked to play the role of Antonio. Dickman is warned that there have been a few alterations made that have solved the legal loophole Shakespeare concocted to allow Antonio’s survival in the original text.

Lionheart, along with his daughter (Diana Rigg) and the troupe, then cut Dickman’s heart out and set it on a scale of justice, from which he makes a quip about it being heavier than the pound Antonio owed to Shylock, so he cuts an ounce away. Of the reenactments throughout this film, this one wears its influence most heavily on its sleeve and not only casts the victim directly into a role with lines to read but openly acknowledges the alterations made to ensure the critic’s death (especially for a play that otherwise had no deaths).

Richard III (Oliver Larding)

The death scene for Oliver Larding (Robert Coote) is set up by the illusion that he’s at a swanky soirée full of guests when those he’s surrounded by are actually Lionheart’s devoted vagrant troupe, acting as high-class attendees at a tasting party. With his outrageous costume and prosthetic nose, Lionheart drums on about punishments and confronts Larding about the critic’s drunken slumber through his performance. The pieces have come together in the film showing that each critic is dying in a manner befitting the Lionheart performance they negatively reviewed. Major kudos to how well-thought-out the master plan of Lionheart’s “kill all critics” crusade plays out. The Duke of Clarence drowned in a vat of wine in Richard III and Harding is cast to die the same way in a special Chambertin ‘64 reserved for him. After hammering the vat closed with Larding’s body inside, and to add to the subtly playful horn of Michael J. Lewis’ score as the scene ends, Lionheart wonders aloud whether Larding will travel well.

Romeo And Juliet (Peregrine Devlin)

Not an actual death, but instead it seems like a fun excuse to add in a sword-fighting scene that further adds to the flair of this film. De-facto lead critic Peregrine Devlin (Ian Hendry) is enjoy a fencing session when Lionheart reveals himself as Devlin’s combatant, but with all of Vincent Price’s infamously exaggerated annunciations. After removing the button from the end of Devlin’s saber, intense sparring ensues. Immediately once Devlin is cornered, Lionheart launches into an expositional narration about how he survived his pitfall from Devlin’s balcony and that the vagrant troupe helped clean him up; they showed him compassion at his lowest. Lionheart decides to let Devlin go, for now, but the true joy of this scene is seeing “Vincent Price” hop from trampolines, flip through the air, and masterfully disarm his opponent in Romeo And Juliet-style sword-fighting before allowing his enemy to live (just so he can be part of the finale).

Othello (Solomon Psaltery)

Uniquely, this scene doesn’t bring about the death of the critic Solomon Psaltery (Jack Hawkins), but instead engineer’s the murder of the man’s wife at Solomon’s own hands. The physically tense Maisie Psaltery (Diana Dors) simply wanted a deep massage, so Lionheart gives her one of the best massages of her life…and also the last massage of her life. Solomon listens in on his wife’s encounter, fully believing her to be cheating on him (due to a false tip he received). After literally breaking through the door and Lionheart saying that she has had many lovers, Solomon suffocates her with a pillow. While the critic didn’t die himself, Devlin retorts that Psaltery may as well be as he’s now both damned to prison for the rest of his life and plagued with the knowledge that his wife died needlessly at his own hands, similarly done by Othello to Desdemona.

Henry VI, Part 1 (Chloe Moon)

Chloe Moon (Coral Browne—who would marry Price after this movie) was desperate enough to get her hair done that she dared to allow someone other than her beloved hairdresser, Henri, to attend to her locks. Lionheart, playing a hairdresser named Butch, puts rollers in her hair (with suspicious cords attached to them), while his right-hand troupe member sets her feet in a large bowl of water for her “pedicure”. Name dropping Henry VI, Part 1 and specifically calling out the scene in which Joan of Arc is burned at the stake, Lionheart reveals himself to Moon just as her mouth is gagged and the electricity is switched on. She begins struggling and smoking, but her police escort is more interested in a magazine than the blooming smoke and temporary power surge that flickers the lights. Too late, he runs down and sees Moon dead in her chair with her hair burned off and facial cuts and burns, completing her role as Joan of Arc.

Titus Andronicus (Meredith Merrigrew)

It’s never ideal to include pets being murdered in a plot if looking to enamor a character to audiences but, in one of THEATRE OF BLOOD’s hardest scenes to watch, Lionheart reenacts the gnarlier cannibalistic scene from Titus Andronicus that sees Tamora accidentally ingest her children at Titus’ hand, after which she dies.

In this film, the roles of the “children” are played by the prized poodles of Meredith Merridew (Robert Morley), who are force-fed to Merridew until his demise.

Laced with humor and acting as if he’s been cast onto a surprise cooking show, Lionheart and his troupe attempt to lighten this scene, but even with quipping that Merrigew “didn’t have the stomach for it”…this scene is dark.

King Lear (Edwina and Richard Lionheart)

For the finale, Lionheart sets up a special rig to gouge Devlin’s eyes out with heated daggers similar to Gloucester’s blinding in King Lear. Luckily for Devlin, the rig stops just short of gouging his eyes out. In the ensuing chaos when the police arrive, Edwina, Lionheart’s daughter, is hit in the head with his coveted award by one of the vagrants (making her Cordelia in this unintentional reenactment) and he carries her body to the roof of the now-burning theatre. After a final King Lear speech honoring his daughter, Lionheart falls into the burning theatre to his death. Devlin, after losing all of his colleagues, retorts that it was a fine performance on Lionheart’s part, but he “overacted” as he always had throughout his career.

While THEATRE OF BLOOD is often remembered as Vincent Price giving us a “ham sandwich” character—as one of the in-film critics called Richard Lionheart’s acting style—it remains a fun time for anyone who grew up reading Shakespeare in school or simply anyone who loves camp! While the influences of the play vary in degree and are sometimes openly toyed with, the overall adaptation of Shakespearean works into a horror-comedy worked very well and I do hope people continue to discover this gem in all its glory.