7 Fascinating Pieces Of Jewish Folklore In ATTACHMENT

Their meet-cute is precious: In Denmark, Maja (Josephine Park) shows up to a library performance of a Christmas character she once played onscreen and literally runs into Leah (Ellie Kendrick), the Jewish academic from London. Their relationship solidifies fast—in fact, when Leah breaks her leg and needs to return to the apartment building she shares with her mother Chana (Sofie Gråbøl) in England, Maja goes with her. Leah’s family secrets emerge and cast shadows in every direction, obscuring the truth until the bitter end.

When Gabriel Bier Gislason's film ATTACHMENT premiered, I felt like I was finally learning (albeit in the context of entertainment) so much about the Jewish folklore that I knew existed, but had never seen onscreen.

1.

Maja responds the same way I would if someone had asked me if I’d heard of Kabbalah: “Yeah, sure, the Madonna thing.”

The bookstore keeper Lev (David Dencik) responds, “Okay. No, Kabbalah is Jewish mysticism.”

The Zohar (Hebrew for “splendor” or “radiance”) is the sacred text that interprets the mystical aspects of the Torah, which originated in 13th century Spain. According to Nissan Dovid Dubov, “Kabbalah divides everything in this world into either Sitra D’Kedushah (the side of holiness) or Sitra Achra (the side of impurity)—literally meaning ‘the other side,’” and the text that Lev shows Maja in the story is called Sitra Achra.

Not all contemporary Jews recognize Kabbalah as authentic. That’s likely why, the moment that another patron comes into his store, Lev says their conversation will have to continue another day, and explains that Maja is “a goy tourist.”

2.

What initially brings Maja to Lev at the bookstore is finding a tiny scroll rolled up into a hole in a corner, over a pile of salt. He explains that part of Kabbalah is the belief “that the names of God can reveal enormous power. Unlocking the secrets of the universe. Warding off evil.” That’s one reason why most Jews write the name “G-d” rather than articulate every letter.

What Maya has brought to him is the “shemot.” A list of the names of God that functions as an amulet to protect children. What they need protecting from in ATTACHMENT is not revealed until the end, but historical instances of the power of shemot abound.

3.

One such instance is in Lev’s text Sitra Achra. He flips the pages to the title “The Golem.” (This one, I had heard of.) He says, “Golem is a giant monster made of clay by the Rabbi in Prague” to protect the city’s Jews—and brought it to life by writing the shemot, or one of the names of God, on its forehead.

Historically, this happened in the late 16th century (three centuries after the founding of Kabbalah) when the Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel (or Maharal) created the golem Josef (or Yossele) to defend the Jewish ghetto from anti-Semitic attacks and pogroms. He’s said to have made himself invisible and summon dead spirits, among many other stories.

4.

Most of the folklore we see in Attachment are amulets of protection. In another such instance, Chana has positioned a face-down bowl under a bookshelf in Leah’s apartment to protect against demons. These “magic bowls” are a type of amulet from Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) created to protect against “difficulty in childbirth and rearing, illness, poverty… as well as supernatural and human foes” before the Islamic conquest of the region, and they’re sometimes labeled with where they should be stationed in the house, like each of its four corners or in a particular room. Typically, the script on them is written in a square, Aramaic script, starting in the center of the bowl and spiraling out clockwise on the concave surface of the bowl. Descriptions of the bowls in their contemporary texts use the verbs “to overturn” and “to press” which indicates both what is done to the bowls (placed upside down) and to the demons (overpowered).

They also often depict images of bound demons, which is the reason Chana says that she keeps in them in her apartment: “(That bowl) was hand painted by Babylonian Jews,” she tells Maja when it cracks. (For reference, there are only 2,000 of these said bowls in the world. When Maja looks stunned, she admits her joke, saying cruelly, “It’s a replica. I made it. So, it’s not valuable, just irreplaceable.” That scathing jab makes Chana the mother-in-law of my personal hell.

5.

Chana also insists that everyone onscreen wear an amulet of Amethyst. It’s no specialized phenomenon that semi-precious stones have some kind of crystalline woowoo power, but according to the Israeli diamond association, Amethyst packs an extra punch. Historians say that the high priest of the ancient Israelites wore a ceremonial breastplate (“hoshen”), and that the ninth stone in it was Amethyst, representing the warrior tribe of Gad.

Anyone astute enough to realize the connotation (not me! I’m still learning!) of amethyst to warrior protection gets a little distinct foreshadowing for the film’s events to come.

6.

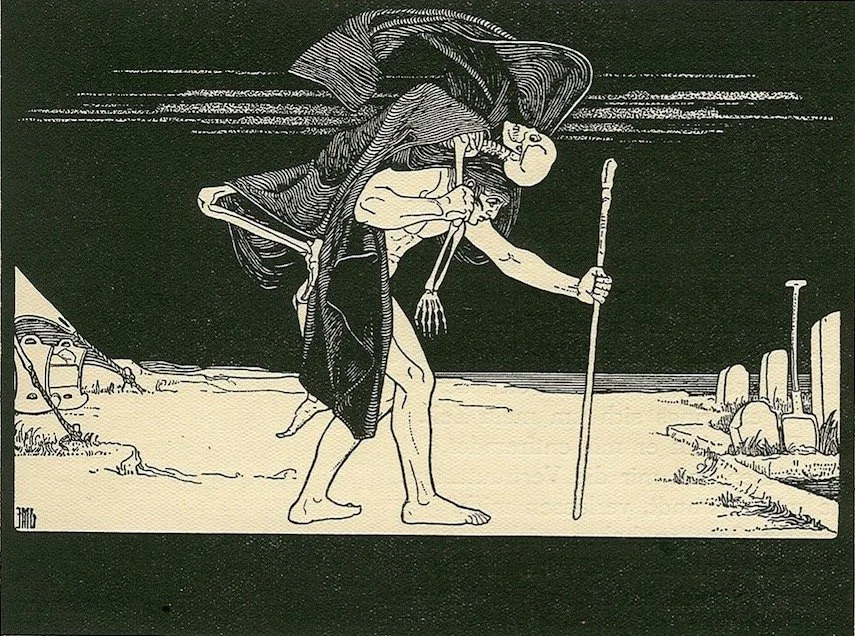

Alongside Golem in the Sitra Achra is the Dybbuk, complete with the illustration by Ephraim Moshe Lilien from the early 20th century, above. Lev describes the dybbuk as “the tortured soul of someone who died.”

Maja says, “Like a ghost.”

Lev, frustrated but patient, replies, “No, it’s not like a ghost at all. The dybbuks possess the body of the living. The only way to expel them or to exorcise them is by finding out who they are or what they want.”

Maja says back, “Like a ghost.” To me, it sounds more like a demon, but it’s undoubtedly in the esoteric space between the two. The Jewish Virtual Library says the term does not appear in Talmudic literature or Kabbalah, and only came to the page in the 17th century as a transliteration of German and Polish Jewish language. Some scholars (like Moses Cordovero) define the term as an “evil pregnancy,” which… I cannot handle.

Some scholars have also said that the only way to get rid of a dybbuk is not by finding out who they are or what they want, but by helping them achieve their goal. (I hate that.)

Either way, this crash course in Jewish folklore establishes the conceit of the film itself…and it is quite the depiction.

7.

Don’t get up without closing your book. Chana scolds Maja for leaving open a book she was reading, and if the books read like Lev’s Sichra Achra, I get it. The folklore states that if you leave your seat without closing your book, a demon might happen by and read it, and then they’ll use that holy knowledge to create chaos. This is by far the most sensible of the superstitions I’ve encountered recently. Knowledge is dangerous. Better to protect it, just in case.

ATTACHMENT will be streaming on Shudder sometime in 2023.