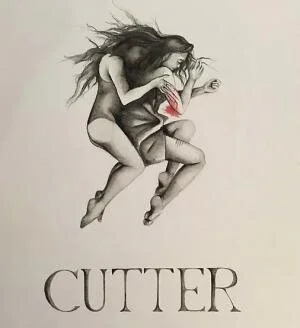

CUTTER (2021)

Disclosure: I am friends (or at least friendly) with many of the people that worked on this short film. I like to think my review is still unbiased and fair, but it would be wrong not to reveal this fact.

I went through a massive Clive Barker phase as a teenager, reading works by and about him. In 1991’s Clive Barker’s Shadows Of Eden by Stephen Jones, Barker discusses why the blood test sequence is the most effective moment from 1982’s THE THING. The writer noted how that scene always elicited a visceral reaction from viewers—not due to its grotesque conclusion, but because of the scalpel going across each finger of the members of Outpost 31. John Carpenter and Rob Bottin covered that set in buckets of blood, gore, and slime as the victims were rendered to pieces by the monster, but none of it landed the same way as that slash on the tip of a finger. Because that was a cut that people could feel. It was a cut people have felt. No alien beast with its talons and fangs can compete with that painful sense memory of skin slicing and bloodletting.

Which brings us to CUTTER, a low budget 15-minute horror film written and directed by Dan Repp and Lindsay Young. It isn’t merely the effectiveness of the flesh slashing in this short that conjured up Barker’s insight, but the fact that these moments of pain in CUTTER are accompanied by other memories. Lack of control, increasing isolation, a crushing sense of abandonment, and more are evident in the film’s scars. That squirming torment felt by viewers isn’t merely due to the genuinely impressive f/x work of Anna Fugate-Downs and Sylvia Ramos (of Hawgfly Productions); it’s the knowledge that the origin of such a cut began inside the woman’s mind, long before a blade touched flesh.

The film opens a young woman (Jen Brown) in the bathroom with many lacerations weeping far too much blood onto the white tile. This cuts to teenage Raelyn (Nadia Alexander) and her mother (Leslie Fender) returning to their apartment. Raelyn is clearly in trouble and her mom is demonstrably exhausted by her daughter. It’s revealed that the young girl is recovering from self-abuse, with scars on her limbs revealing many sessions of mutilation. But soon there is a new cause of these slashes as the specter of that initial woman from the intro appears and cuts Raelyn’s flesh anew.

As with any movie, there are constraints under which the filmmakers must work (even more so as a low budget short). CUTTER succeeds under those parameters thanks to Alexander’s lead performance, the visuals for the ghastly parts of the tale, and a keen sense of emotional knowledge.

Alexander doesn’t get to display a ton of range in the short—Raelyn is essentially that common reduction of angsty and frightened teen—but she imbues her performance with a realism even within such confines. Most teenagers are sarcastic jerks that don’t really understand how to communicate their emotions properly, all while being under the authority of adults who somehow also expect them to act like grown ups as well.

This unfocused anger is tied to her own fear of this spectral creature; Raelyn doesn’t really understand what is happening or why and so her emotions lack any real focal point. Alexander conveys this sense of being adrift on a sea of troubles very convincingly. Her performance ties this all back into the (common) impulses surrounding cutting: a need to express some feeling but not sure how or why, and to feel in control of something.

The ghastly bits of CUTTER start with Brown as this menacing spirit. The actor does very impressive work in her mute role with a physicality that’s not too performative, but feels contradictorily, yet simultaneously, authentic and unnatural. This is furthered by the exceptional f/x work by Fugate-Downs and Ramos. Not enough can be said to praise their work on Brown’s make-up and prosthetics as well as the realization of the cuts across the bodies of the actors.

It’s not perfect though, with some fingernail prosthetics that aren’t as polished as the rest of the work and thus a bit distracting. And yet there remains a lot of exceptional work on display. Not to get too gruesome, but the biggest coup the f/x team delivers is found in the bloodletting and wounds. It’s remarkable how they handled blood coming out of these cuts—flowing continuously and in great volume, but languidly so as to draw out the sense that something is slowly being emptied out.

All of this bolsters the insight and emotional honesty the filmmakers impart throughout. It’s a sensitive subject that can be easily sensationalized or awkwardly fumbled. Repp and Young avoid those pitfalls by approaching the issue sincerely. CUTTER doesn’t condone the destructive behavior but presents it as a part of Raelyn’s life; clearly harmful but without inviting judgment on the girl.

Unfortunately, that same empathetic approach is missing in a very minor story element involving the reductive path of treating psychiatric drugs as inherently evil or insidiously manipulative. To be fair, this is mostly a personal peccadillo, but it still feels at odds with the nuances found in the rest of CUTTER. It’s also far too reminiscent of the dynamic between Kristen and her mother in A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET 4: THE DREAM MASTER.

The short film also has a few technical issues that detract from its accomplishments. Most scenes are extremely brightly lit to the point of being a bit too harsh on the actors’ features and their surroundings. It was clearly a conscious choice—perhaps evoking realism, eschewing the literal darkness of most shorts (used to cover up shoddy f/x and/or low budgets), or to show how this struggle in plain sight. But no matter the intent, it throws off the color temperature of the shots and the film would benefit from a bit more natural level of illumination.

The other pronounced flaws are found in the cinematography/editing. To convey how medication impairs Raelyn, two effects are employed that are visual shoddy and overused in other projects. The first is that trailing effect where each movement leaves behind an aftereffect of the path, showing perception is slowing down. This has been a go-to for drug simulation for many years and never plays well. The other poor photography (or perhaps editing) choice in CUTTER is the use of a pseudo-slow motion type filter (the kind once found on camcorders) in a couple of scenes that alters the frame rate but has a side effect of making the footage herky-jerky. It’s a small matter, but it certainly cheapens the moment and feels like a compromised decision.

CUTTER is a unique and effective take on themes far beyond the titular subject matter. It is the appropriate length for the story and couldn’t sustain anything beyond its 15 minutes, especially with such a rudimentary storyline. But that simplicity allows the filmmakers to inject nuances into the characters and the f/x to create something much more affecting than most haunted films. The technical shortcomings and occasional reliance on tropes are few but can slightly mar the experience. As Barker pointed out about Carpenter’s work, CUTTER will have viewers cringing at each slice of flesh but also reeling from the deeper pain of isolation and despair.

CUTTER is playing as part of the Chattanooga Film Festival, a virtual genre film festival that runs June 24 - June 29. Learn more and buy tickets here.