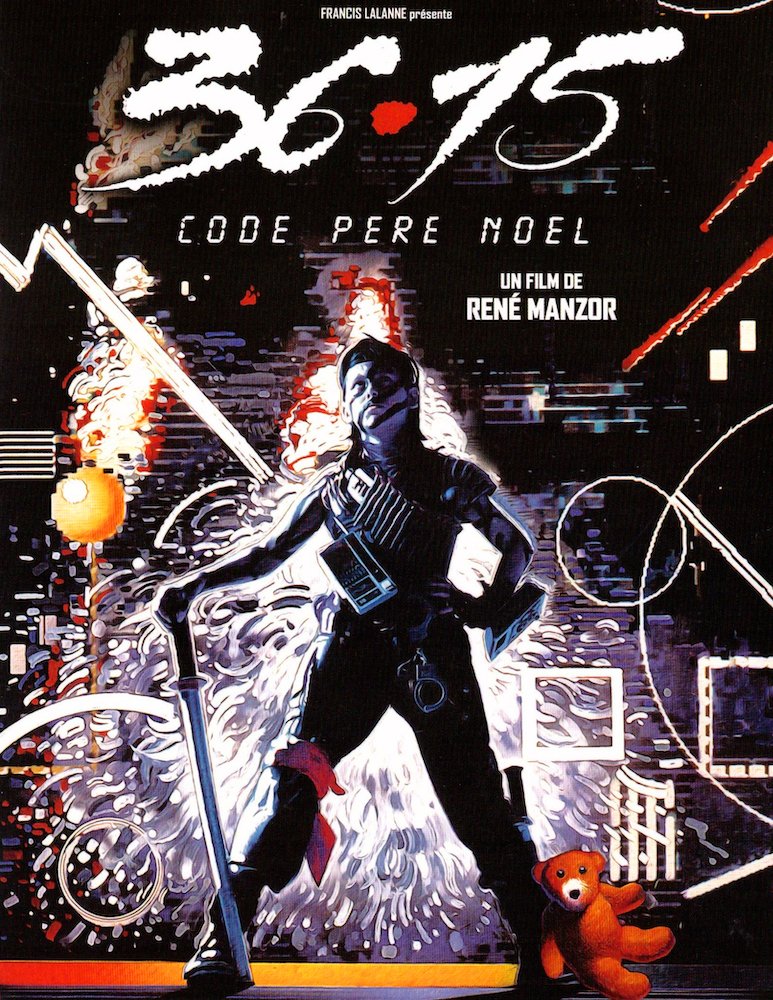

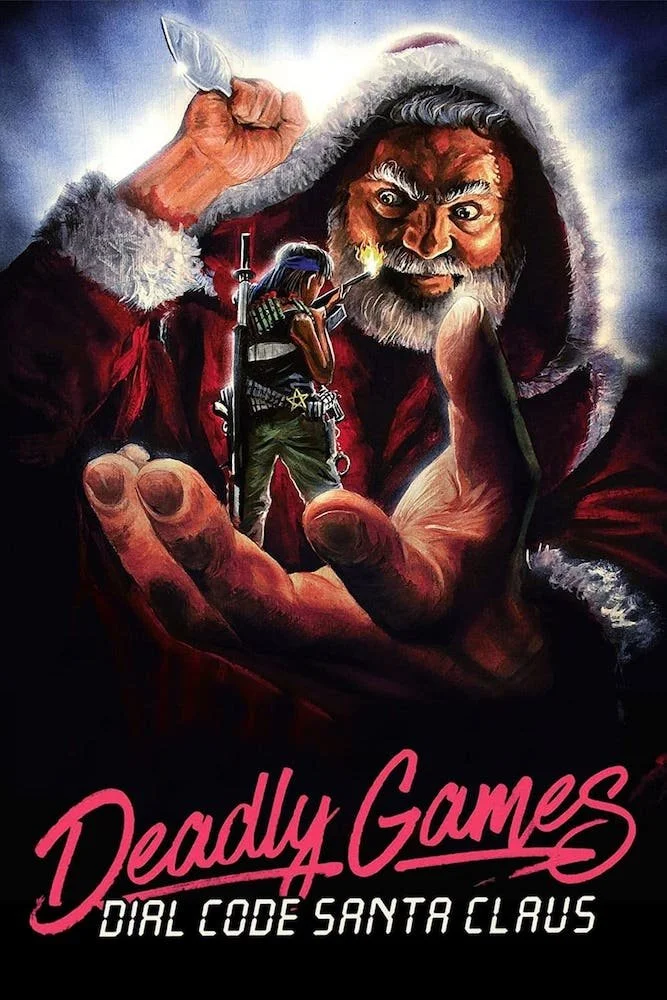

DEADLY GAMES (1989)

The Real War On Christmas

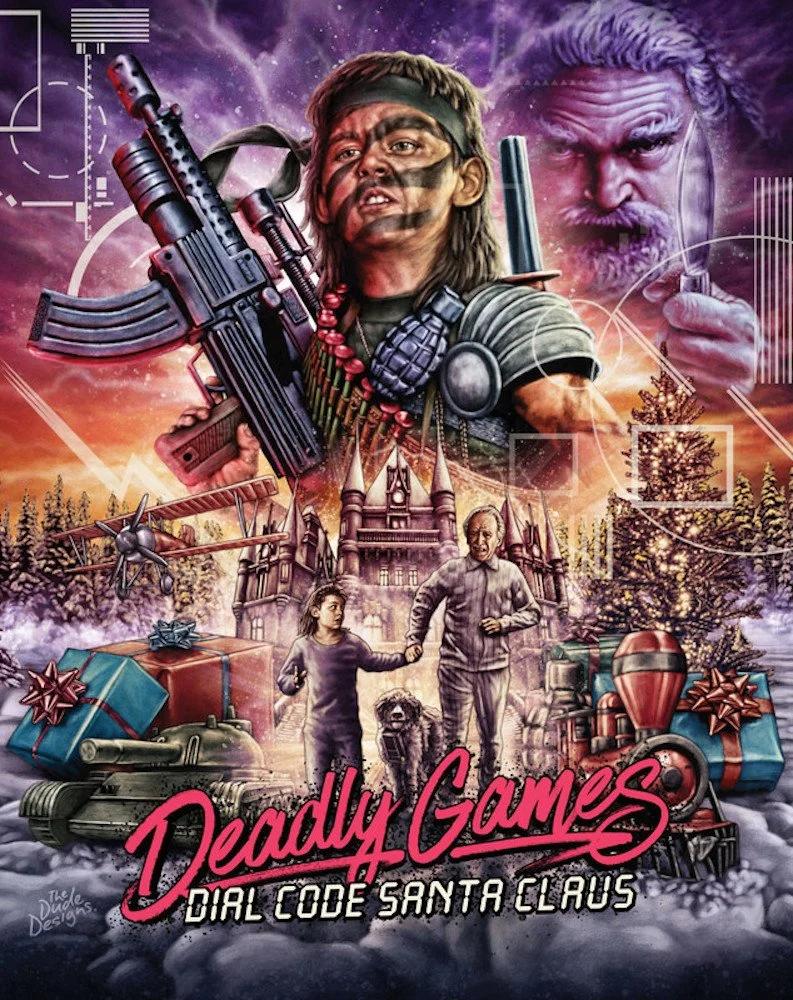

DEADLY GAMES (a.k.a. DIAL CODE SANTA CLAUS a.k.a GAME OVER a.k.a 36.15 PÈRE NOËL), directed by René Manzor, is a cult Christmas horror film often referred to as “the French HOME ALONE.” Which is unfortunate as it predates HOME ALONE (1990) and has a wildly different tone. There are the obvious similarities—a child booby trapping the home against invaders, a very sad mom, and Christmas. Yet to label it in relation to an American film audiences recognizes does a huge disservice to the degree of DEADLY GAMES’ heaviness, drama, and horror.

If anything, it is the antithesis and bitterness to the beloved saccharine of John Hughes. While HOME ALONE wraps up with Kevin reaffirming his belief in the magic of Christmas, DEADLY GAMES details in brutal and heartbreaking fashion how the moment we stop believing in Christmas magic is the moment we lose our innocence. The real war on Christmas is not in how we celebrate the holiday; it’s the battle we fight to keep believing it matters and what that belief costs us.

DEADLY GAMES isn’t devoid of humor. It has some entertaining nods to the over-the-top melodrama of 1980s action films.

There are times this tongue in cheek absurdity awkwardly collides with the gravity of sadness, but overall Alain Lalanne’s performance as Thomas has so much sincerity and vulnerability that it keeps the balance in check.

This movie feels like if Tim Burton watched DIE HARD and RAMBO, knew about HOME ALONE, then said “how do I Roald Dahl the shit out of this?”

The audience starts the movie getting a feel for our protagonist Thomas. He is a child prodigy who is close to his diabetic grandfather and widowed mother. He is also still deeply grieving the loss of his soldier father and coping through make believe.

He vehemently believes in Santa Claus and fantasy while managing the role as man of the house.

Viewers see this illustrated in how Thomas repeatedly lies to his grandfather about the severity of various situations to not worry the old man but protect him instead. The blend of the childish and responsibilities is evident when Thomas is talking to his dog JR, telling the pup not to stay up so that JR doesn’t get in trouble with Santa and still get presents. It is both endearing and sad. Manzor depicted this blurring of childhood and adulthood by creating dream-like sequences along with a stunning visual house design. Throughout DEADLY GAMES, I often questioned how much of this narrative was real and not simply Thomas’ imagination.

As the movie progresses, audiences watch as Thomas’s innocence shatters before them. First, he has to witness a man that appears to be Santa murder his dog. Later, Thomas is stabbed and chased out onto a roof by his formerly beloved magical figure turned maniacal assailant Father Christmas, and the boy screams out for his mother as tears run freely down his cheeks. When faced with the opportunity to shoot this sadistic Santa Claus is another point in the film where we see he is still conflicted with what is actually happening.

Even in the end, after all the traumatic bloodshed, Thomas still believes it was he who caused Santa to turn evil. Is this a child’s logic at work, or is it partly that this alternative was better than believing that Santa and Christmas magic was a fabrication? I can say as a trauma survivor myself, one of the ways we gaslight ourselves in order to survive is to believe that we have some sort of control over the chaos and pain. This is more comfortable than accepting that pain can be caused without rhyme or reason—or simply out of cruelty. For many, guilt is an easier pill to swallow than hopelessness.

Viewers get the opposing side of Christmas as well. The mother (Brigitte Fossey) is straddling a similar line on what Christmas means to her. On the one hand, it was important to her to make sure her child and other children still believed in Santa. Yet, she was eager to work past midnight at her shopping center on Christmas Eve instead of going home to her family—to her, Christmas is a commercial fabrication whose monetary value cannot be downplayed.

Then of course there is the villainous Santa Claus, skillfully portrayed by Patrick Floersheim.

This nameless character (billed only as Le Père Noël or “Father Christmas”) frightens because he is completely unhinged. There’s an argument to be made that a possible motive for his violence (aside from mental illness) is some kind of trauma that happened to him where he has a child’s mentality and worldview.

Multiple times throughout DEADLY GAMES, it is shown that evil Santa is triggered by children rejecting him when he tries to join their games. In an early conversation with Thomas, evil Santa asks twice, “Do you want to play a game?” Later in the movie, Santa catches Thomas and releases him in order to continue playing Hide and Seek. When Thomas calls for help through the police scanner, evil Santa furiously yells, “You cheated!”

In some twisted logic, he was “playing” with Thomas, and was possibly creating this violence to avoid feeling lonely. This is not too far removed from the elaborate war fantasies that Thomas enacts earlier in DEADLY GAMES, and provides much of his weaponry when facing off against his festive foe. But evil Santa is an adult, and doesn’t have the luxury of indulging in such reveries—he should know the difference between fantasy and reality. Therein lies the rub about Christmas magic and similarly themed movies.

The belief in Christmas magic asks us to blur the lines of fantasy and reality. It asks us to surrender to a moral and righteous belief that justice and goodness will always prevail at least once a year. As an adult, this seasonal window of wholesome hope can provide a breath of fresh air to a stale soul. For many children, it is simply the truth…until it is not. There is pain in that, too. There is also loneliness. For while the world has decided to come together and believe in an unspoken treaty of being kinder and exploring wonder, there will always be the outliers. These people find that their loneliness and sadness gets magnified against the backdrop of everyone else’s joy and hope.

That quote you always hear about the suicide rate climbing around the holidays isn’t just some water cooler talk factoid (and it isn’t even necessarily accurate).

But that concept rings true to many because it is a quantifiable expression of the intensity of Christmas melancholy.

I wish the idea that it’s okay to be sad during that time of year were more normalized. December’s array of holidays can be a time of joy and love. It can also be a trigger of sadness and anger. Christmas is very complicated, because people seem to forget that life doesn’t actually stop for magic. There isn’t always a happy ending. This is where DEADLY GAMES shines.

I wouldn’t recommend this film to anyone who wants to feel warm and cozy. But if you’re a person who gets sad around these days, and maybe you don’t quite know why, then this movie could be for you. It is for the people who feel attacked by the holiday. The real war on Christmas is what we do to ourselves for the sake of it. It’s asking a lot to put an entirety of a person’s hopes and dreams in one season, let alone one mythical figure like Santa Claus. It can be hugely disappointing in a way that people refuse to talk about. You will survive Christmas. Unfortunately, that might mean getting rid of a bad Santa here and there, in order to place faith in yourself instead.